Jessica Nothdurft's latest exhibition Dreams and Nightmares uses her signature faux naïf styling to explore her evocative and raw life experiences. The show centres on hyper-restrained ink drawings, bronze sculptures and paintings; battered housewives, pregnant dogs, cages and crouched forms recur in the series. The poses and graphic depictions link the characters' relationships, creating a solid narrative around the explored reality of shame.

Dreams and Nightmares is a raw, honest glimpse into the artist's method of processing life experiences and comes with a mature audience warning as it deals with themes of abuse and depicts nudity.

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

Download the exhibition catalogue here.

Sold

Sold

The Cage 2023

Oil on timber panel Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame.

61 x 40.7 cm

$850 Sold

Sold

Sold

The Lacy Kind 2023

Oil on timber panel Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

40 x 61 cm

$850 Sold

Sold

Sold

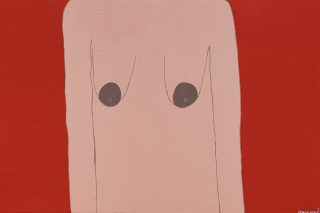

Heavy Tits 2023

Oil on timber panel Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

61 x 40 cm

$850 Sold

Sold

Sold

Human Milk 2023

Oil on timber panel Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

61 x 61 cm

$850 Sold

Sold

Sold

Ram Ram 2023

Oil on timber panel Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

61 x 61 cm

$850 Sold

Sold

Sold

Two Bitches 2023

Oil on timber panel Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

61 x 40.5 cm

$850 Sold

Sold

Sold

Mercy 2023

Oil on timber panel Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

61 x 40 cm

$850 Sold

Sold

Sold

Wilted 2023

Oil on timber panel Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

61 x 40 cm

$850 Sold

Sold

Sold

The Yucky Things 2022

Oil Paint, Synthetic Polymers paint and glitter on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

57 x 76 cm

Contact gallery for enquiries Sold

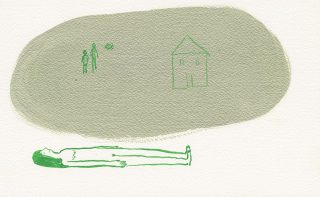

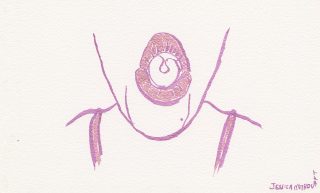

Akimbo 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Framed

Sold

Sold

Fever Dream 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

25 x 15 cm

$500 Sold

Sold

Sold

Keep Quiet 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Sold

What A Pretty Girl 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Framed

For Shit’s Sake 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Framed

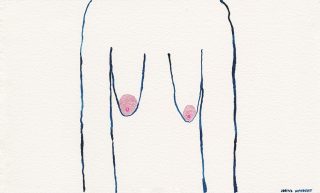

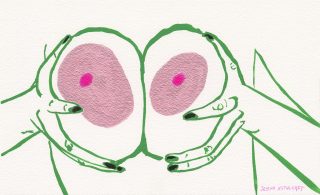

Heavy Tits (ink) 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Framed

Sold

Sold

Mercy (ink) 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Sold

Sold

Sold

Ram Ram (ink) 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Sold

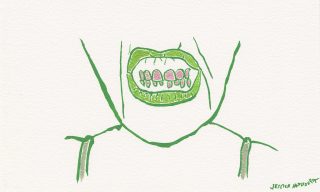

Rolling Tongue 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Framed

Sold

Sold

Squished Tits 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Sold

Preggos (ink) 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Framed

The Tension 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Framed

Wilted (ink) 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Framed

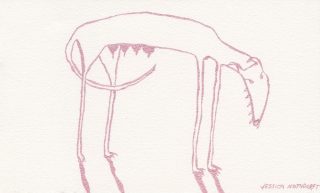

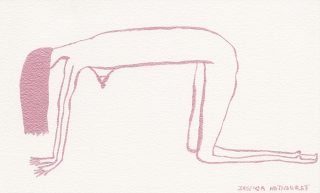

Crawl 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

15 x 25 cm

$500 Framed

Sold

Sold

The Lacy Kind (ink) 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

25 x 15 cm

$500 Sold

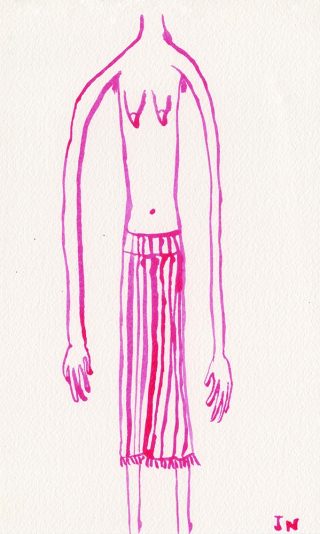

Topless Housewife 2023

Ink Drawing on 300 gsm Arches Aquarelle Paper. Framed in Raw Tasmanian Oak timber frame

25 x 15 cm

$500 Framed

The Cage (Bronze) 2023

Bronze, hand sewn House dress, human hair wig

Cage: 32 x 32 x 32 cm, Figure: 6.5 x 21 x 5 cm

Contact gallery for enquires

Dissociate with me (Bronze) 2023

Bronze and antique glass eyes

11 x 9.5 x 5 cm (each)

Contact gallery for enquires

Crouching figure (Bronze) 2023

Bronze, human hair wig

23 x 25 x 6.5 cm

$2200

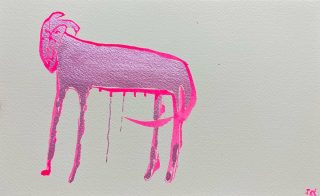

You have to learn to stand on your own four feet 2023

Bronze

10.5 x 25 x 14 cm

$2200

Black Heart Your Heart My Heart Artist Book 2023

Bronze, dyed natural silk

154 cm x 120 cm, Book closed: 16.5 x 18 x 3.5 cm, Book Open: 31 x 18 x 5.5 cm

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view